Steps We Must Take Before an AV Kills a Child

I asked five experts with insight on AVs, AI, transportaion and safety. "Given a magic wand, what would you do to ensure safer AV implementations in 2025 and beyond?"

The deployment of robotaxis, ready or not, is a fait-accompli. It will only accelerate until a child gets killed by a machine driver someday, somewhere, triggering a wave of belated public outrage.

Nobody should wish for so tragic an outcome. But if you believe it will never happen, think again.

Tesla’s Full Self Driving (FSD)-related fatalities have already prompted a federal investigation. Lawsuits filed against Tesla have increased in parallel with a rise in Autopilot accidents.

But, then, who’s counting?*

(*editor’s note. You can see the list of Tesla Autopilot crashes here.)

Autonomous vehicles (AVs) will proliferate, and technological advancements will march on. The AV industry will cling to its misguided AV mantra that machine drivers are “safer than human drivers.”

In a world where the former geeks of high-tech are now deemed cool, the most urgent question to ask about AVs is not “When?” It’s “What are we going to do about it?”

By “we,” I mean corporations, the media who cover them, engineers who develop technologies, policy makers, regulators and community advocates.

Today, tech reporters are focused on tech-spec wars – tera flops, mega pixels, point clouds, MLPerf benchmark scores and power and thermal demands. They write about types of sensors, the growth of vehicle compute power and artificial intelligence progress like Tesla’s “end-to-end” AI, which is said to instantly translate images acquired by vision sensors into driving decisions.

Most reporters, however, fail to query evident gaps in emerging technologies.

The chronically unasked questions touch on engineering, law and society. Who is watching to see if robotaxis adhere to safety standards? Who’s held responsible when technologies go haywire? Who decides which machines are allowed on streets that belong to the public?

I don’t pretend to have answers. I resort to experts with insight on AVs, AI, transportation and safety. These include:

• Bryant Walker Smith, professor, School of Law and (by courtesy) School of Engineering at the University of South Carolina

• Bill Widen, professor at the University of Miami School of Law

• Phil Koopman, embedded system software & safety, self-driving vehicles, professor at Carnegie Mellon University,

• Peter Norton, professor at the University of Virginia

• Missy Cummings, robotics and artificial intelligence, professor at George Mason University

I had one question to all: Given a magic wand, what would you do to ensure safer AV implementations in 2025 and beyond.

The AV and media

Bryant Walker Smith authored a 2021 paper, “How Reporters Can Evaluate Automated Driving Announcements.” He posed questions reporters should ask to “facilitate more critical, credible, and ultimately constructive reporting on progress toward automated driving.”

In my interview, Smith went further. “I wish media didn’t just focus on technology,” when reporting on the readiness of AVs.

Whether technologies pitched by companies work as claimed isn’t easy to answer. Technology is constantly changing and, given enough time, usually improving. This is dog-bites-man.

Media attention should, instead, focus on “trustworthy companies,” said Smith. Can companies developing technologies be trusted?

Is such a yardstick too subjective? Reporters already have a public record of corporate claims to compare to actual achievements—or failures.

Companies serious about building consumer trust should seize every opportunity to tell media not only what their technology will eventually accomplish, but also where current technology still falls short.

A company transparent about its technologies’ pros and cons can more credibly strut its stuff when it overcomes those limitations.

One more thing: Reporters too often overlook the AVs’ Operational Design Domain (ODD).

ODD describes when and where a vehicle feature is specifically designed to function. As Smith described, a feature might be designed for freeway traffic jams. Another might be designed for a particular neighborhood in good weather. Without accurately disclosing a level of autonomy coupled with specific ODDs, it’s hard for media to report on the promised readiness of AVs.

The AV and liability

Often glossed over among AV advocates and the media are liability issues.

Law professor Bill Widen is emphatic on this point.

“The most urgent matter is law reform to clarify the attribution of financial responsibility for accidents involving automated vehicles,” Widen said, “particularly amounts potentially owed to ‘involuntary’ creditors.”

“Involuntary creditors,” he explained, are “vulnerable road users, such as pedestrians, cyclists, drivers/passengers of conventional motor vehicles, first responders,” the people who did not sign up to get engaged with vehicle automation technology.

“When an automated driving system (ADS) fails to function properly and an accident occurs, the AV manufacturer should bear the cost of that accident. Imposing tort liability on the AV manufacturer creates systemic pressure to continually develop safer products,” Widen said.

Widen calls the issue “duty of care.”

“If the automated driving system failed to perform to the standard of conduct the law requires of a human driver in the same situation, then liability should result for the AV manufacturer.”

The law should impose a "duty of care" owed by the ADS to other road users, he stressed. “When the ADS breaches that duty, and an injury follows, liability attaches — just as it would to a human driver for negligent or reckless driving. The AV manufacturer should be the party responsible, rather than the owner of the AV, because only the AV manufacturer can improve performance of the ADS in the AV.”

Widen noted that the AV or ADS is not a legal “person” who can be responsible.

Widen made clear that he isn’t talking about “conventional product liability statutes.” Such rules cannot be practically applied “given the difficulty of proof of causation between the details of the operation of neural network operation and the accident, and the paucity of experts capable of providing relevant analysis and experts.”

Widen’s “duty of care” argument seems like “common sense,” but it isn’t where the law stands today. AV industry’s lobbyists have been encouraging state legislators to shield AV companies from liability.

Asked for a second wish, Widen said, “I would want the law to clarify the liability of ‘voluntary’ users of AV technology.”

The case in point is “the owner/operator of an AV who uses it to pilot a trip home after drinking at a party. He said that any states assign liability to the person for an accident “based on the ability to control the AV even if the owner/operator does not exercise that control.”

“This result would shock owner/operators of highly automated AVs (i.e. Levels 4 or 5),” said Widen, “particularly because vehicle automation technology's signature use case is eliminating fatalities due to drunk driving.”

The AV and safety standards

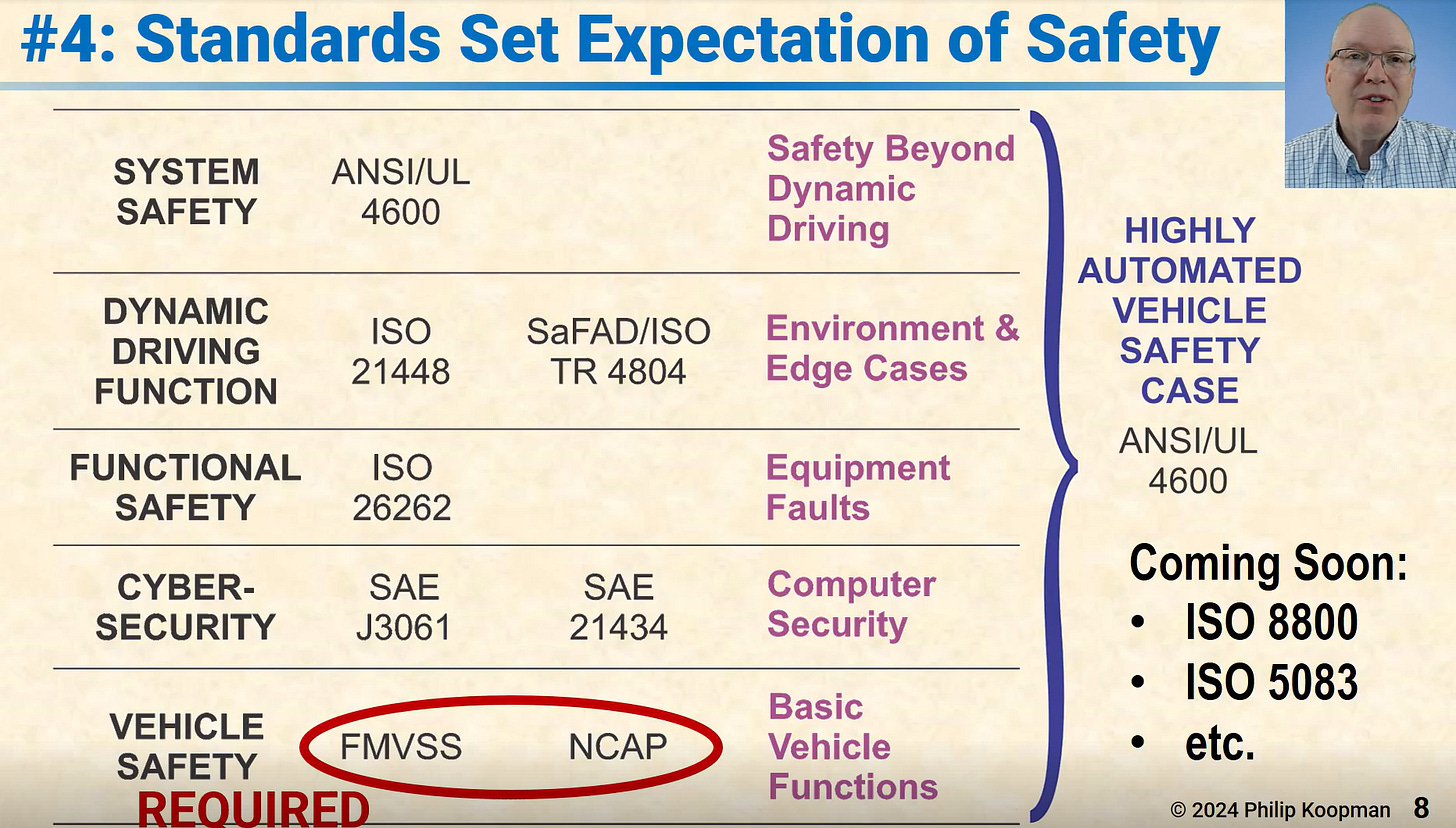

For safety expert Phil Koopman, the top of his wish list is AVs’ conformity to industry standards.

The claim that “regulations stifle innovation” is boilerplate among tech companies. Koopman calls this a myth. “You can easily have both innovation and regulation, if the regulation is designed to permit it.”

The imperative to follow safety standards instills “a reasonable belief that our engineering efforts have established safety before we even do validation.”

For all vehicles, safeguards are available, including Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards (FMVSS) and the new car Assessment Program (NCAP), which apply to basic functions. “They're not really about software safety. They're about whether the brakes work, and the headlights are good, and the air bags and things of this nature,” Koopman explained. “They don't prove you're safe, but they set a minimum standard.”

Shown in the chart below, “There's cyber security standards. There are functional safety standards (ISO26262), which, in simple terms, make sure that either a computer-based function is working properly or it turns itself off so that something else can take over,” noted Koopman.

Dynamic driving function standards are “about dealing with all the weird things that happen out in the world. Have you thought of everything? … Have you mitigated all the hazards?”

There are system safety standards because drivers do more than drive, Koopman aded. A robotaxi has “a lot of other safety considerations to think about,” including “how you assess whether your safety case really has everything in it.”

Keynote: Understanding Self-Driving Safety

The big question, however, said Koopman, is whether companies are following these rules. Officially, the only requirement is to follow the government mandates—FMVSS and NCAP. All other standards are optional.

When pressed, companies will offer lip service, but do not say that their vehicles conform to these standards.

Koopman noted, “Most engineers will tell you in a private conversation that they're doing as much as they can [to meet] these standards. But that's not quite the same as independently assessed performance.”

Bear in mind that the automotive industry “is unique.” Despite building life-critical products that face well-known hazards, the industry is not required to follow its own standards.

The AV and public streets

Historian Peter Norton’s emphasis is one basic principle: “Streets are public property.”

He was quoting George H. Herrold, the city planning engineer in St. Paul, Minnesota, who said in 1927 that streets are “not to be abused but to be used with convenience for the good of the greatest number.” Norton said this principle was “ubiquitous in US cities a century ago.”

Plan of St. Paul, the Capital City of Minnesota (1922)

So, what changed?

In America, “private companies have been making public policy for a century. They conceive plans that serve their business interests and then find ways to release them on our public roads and streets – making experimental test subjects of us all.”

Norton said, “That’s why we have a transportation system that millions can’t afford, that keeps people in debt, that makes a driver’s license practically mandatory, that’s unsustainable, and that is far more lethal than that of any other high-income country.”

Norton stressed: “And yet still we let companies make our transportation policy for us – including our policies for robotic vehicles.”

Norton’s advice?

It’s time to reverse the relationship between public agencies and private companies. “We need public servants to make public policy in the public interest.”

This sort of commitment to the public—not shareholders or the market—has resulted, Norton said, in fireproof public buildings, sanitation systems, and safe drinking water. “That’s also the principle that ensured that every American city of a century ago had an extensive street railway network with frequent service at low fares.”

But, “For almost 100 years, private companies, and the investors behind them, have been making public policy in our streets. Companies come to cities with transportation projects that constitute experiments in public policy. If they don’t get what they want, they get a state authority to overrule the city.”

Curiously, in these experiments, “Is it safe?” becomes a decisive question. Yet, “We let the companies do most of the answering,” Norton said.

What we must ask, said Norton, is: “Does it serve the public interest?”

The AV and AI

Among robotics and AI experts steeped in autonomous vehicle issues, nobody beats Missy Cummings’ candor.

Leveraging AI inside the cockpit for entertainment or vehicle information is harmless. But when advanced AI — such as Tesla’s end-to-end (ETE) AI or LLMs (pushed by Waabi) — applies to an AV’s decision making, what then?

There are, of course, industry fanboys and financial investors eagerly mounting the ETE AI bandwagon.

So, I asked Cummings if Tesla’s ETE or LLMs, will improve AV performance. She wrote back bluntly: “No, both ETE and LLM-based AI will certainly result in death. Any form of GenAI should NEVER be used in a safety-critical system.”

Why? What’s the problem?

“Neural nets always regress to the mean/most frequent state based on the training data. Thus, any ETE approach will not necessarily be able to resolve high uncertainty.”

In her recent technical paper, “Identifying Research Gaps through Self-Driving Car Data Analysis,” she wrote: “Computer vision systems are very brittle and likely play an outsized role in crashes. Self-driving cars also struggle to reason under uncertainty, and simulations are not effectively bridging the physical-to-real-world testing gap. This analysis underscores that research is lacking, especially for artificial intelligence involving computer vision and reasoning under uncertainty.”

Below is a brief video produced by the World Economic Forum. Cummings discusses use cases for self-driving vehicles and her key issues for self-driving companies. Her incisive summary on AVs is instructive.

World Economic Forum video: “The Autonomous Mobility Revolution”

Do no harm is the responsibility we face in bring technology to market.

Fictional capabilities belong in print or online, not controlling vehicles not PROVEN safe.

I agree with all of your article's points and these struck the chord of basic fudiciary responsibility:

1. Bill Widen, law professor University of Miami, “Involuntary creditors,” he explained, are “vulnerable road users, such as pedestrians, cyclists, drivers/passengers of conventional motor vehicles, first responders,” the people who did not sign up to get engaged with vehicle automation technology.

2. George H. Herrold, city planning engineer in St. Paul, Minnesota, said in 1927. "streets are “not to be abused but to be used with convenience for the good of the greatest number.”

3. MIssy Cummings, professor of Robotics and AI, George Mason University "Any form of GenAI should NEVER be used in a safety-critical system.”

If the manufacturer doesn't accept responsibility for results of their decisions, then the vehicle owner and operator are next in line to make those whole who suffered loss due to bad AI choices. We fine and jail drivers, and business owners today for liability . . e.g. Opiods

Junko, I mourn the early deaths of the 44+ noted in your Wikepedia reference. Families losing someone to AI is shameful.